Anna Bhau Sathe

A prolific writer and a performer-activist who crisscrossed the ideological landscape of Marxism and Ambedkarism.

Born in the year 1920 in village Wategaon of Satara district of Maharashtra in Mang community, Anna's life journey is just not about a person who is devoid of higher education but still presents us with a canon of work that spread across more than 30 novels, and a travelogue.

Mang caste has been placed in the lowest levels of the caste hierarchy with untouchability imposed on them. They formed part of the Balutedar system that existed during the period of Peshwa. Also they were forced to do Vethbigari (forced labour). Mang-Matangs were below the social level of the Mahars who during the colonial rule joined the British Army. Yet Mangs revolted against the British. Lahuji Salve is an example. Mangs were declared as a criminal tribe by the British in the 19th century. Many members of his community were tamashgirs or performers.

Having walked with his father from Wategaon to Bombay in search of work, Anna ended up in Matunga Labour Camp where several others like them resided and worked in the cotton mills or as sweepers with the Municipal Corporation or in other factories and shops. Matunga Labour Camp where the journey of his political education started, also gave him a platform to express his skills as a poet-singer. In the late 1930s, members of the then Communist Party used to organise Study Circles at the Labour Restaurant which exists even till date. One of his first plays was a satire on the Plague disease and the world around it.

Communists arranged for a shanty across the Matunga railway station where he could stay and write. An anecdote goes that Shankar Narayan Pagare, a party member would needle and cajole Anna to write for which he would pay him Rs 5 for every song and a shirt for every play. Bombay also gave him the opportunity to learn from the cinemas that he would regularly watch, and Bajrang Korde writes that the film posters became his alphabet books.

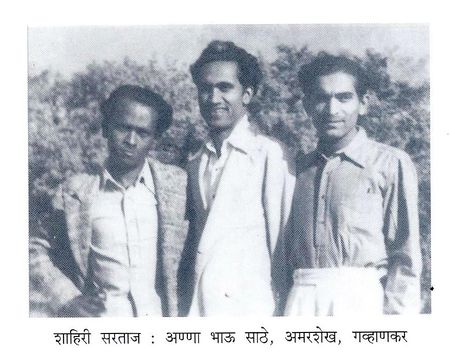

By the year 1944, Anna along with Shahir Amar Sheikh, D N Gavankar formed the Lal Bavauta Kala Pathak-Red Flag Artist Troupe. He would write most of the songs that were sung by Amar Sheikh and plays that were performed by them together. They used to be in the form of Tamasha that was by then known as Lok Natya and revolved around the themes of spreading ideas of Marxism, a critique of Congress’s nationalism and what communism meant. Most of the these were performed in the workers chawls or in rural Maharashtra.

The World of his Writings: He was writing during times when experimentation was happening in the literary world. A little earlier than him, in Maharashtra we had Jyoti Phule who introduced the social realm that was absent in literary works of those times. One can also say that a work of art cannot be a statement that is rooted in ideology. If it is in the realm of realism then more than ideology, the work is what the artist sees and feels and wants to emote and express.

..... “the author must live with his people. The artist that lives with the people is the artist the people stand by. The author who turns his back on people will find that literature has turned her back on him. As every artist knows, art is like the third eye that pierces the world and incinerates all myths. This eye must always be alert and must always see for the people.” (From his Speech during the First Dalit Sahitya Samelan, 1958) In 1942, following the severe drought that ravaged West Bengal, the Indian Performing Theatre Association (IPTA) organized a programme to raise funds for the drought affected. It was for this performance that Annabhau composed Bangalchi Hak, a povada that became very famous in the Bombay theatre circuit at that time.

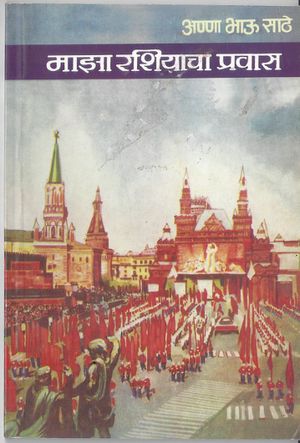

In 1961, the Communist Party organized a tour of Russia. The workers of Bombay came to see Annabhau off. As he was leaving, they asked him to go to Russia and see all the slums and come back and describe them. When in Russia, the members were asked what they wanted to see while they were here. Some wanted to see the Kremlin, others the Moscow Museum. Annabhau told his guide he wanted to walk on the footpaths and see the people. He was already famous in Russia as the Russian translation of his povada Stalingradcha Povada had been a huge success. The trip inspired the writing of a travelogue that helped further global proletariat consciousness.

Annabhau’s activism was not limited to the artistic realm. He was an excellent organizer of people and a mass leader in his own right. His egalitarian and emancipatory discourse appealed to the people. His close links and understanding of the harsh realities of Dalit and working class life gave his activism and leadership respect and legitimacy. In 1947, on the eve of Indian Independence, Annabhau led a massive rally of workers bearing black flags. The march condemned the impending independence as false and slogans brought to light the plight of workers and Dalits. His intellectual work contributed to and drew inspiration from anti-caste and anti-class philosophy and movement. He also provided cultural leadership to the Unified Maharashtra movement.

His works are representative of the hope of the egalitarianism and a utopia. Annabhau’s plays, novels, povadas, short stories, and lavnis form a single body of work. The genres of his work chronologically as follows; Povadas, songs, plays, short stories, novels and a travelogue in 1968. Povadas: The povadas deal extensively with the productive facets of the rural and urban. He distills micro-situations that are common occurrences and yet were till-then unspoken. Annabhau has dedicated to struggles and histories that have inspired people on a global scale, Stalingradcha Povada (Stalingrad’s Povada) written in 1942 he puts together a fascinating rendition of the events of the Second World War. Describing the rise of Nazi capitalist Germany, he tells of the invasion of Russia. The povada is of epic proportions but boils down to Annabhau distilling the spirit of resistance and the emotion that drove the Russian revolution. He sets up the war as an attack by the fascists on the workers and shows how the Red Army responded to the brutal advance of the Nazis in Russia. The povada is a brief history of the Second World War but is used to extremely good effect by Annabhau to draw a parallel to the Dalits on a global canvas that was as yet untried. Benaglchi Hak is not only a warning, but also a social history. It is not only an attempt at creating global workers’ consciousness. Annabhau draws inspiration from non-Maharastrian sources and yet he is at the same time creating responsibilities, sites that must be preserved, which must be fought for. Many of his povadas can be seen as creating a pan-Indian consciousness. In 1944, Annabhau writes Bengalchi Hak (Bengal’s Call) as an appeal to help the famine stricken in Bengal. Annabhau paints the most pathetic picture of famine, of want, of sorrow, of the hoarding rich. Of those leaving hearth and home and selling what little they have to go in search of food. Some dying by the roads of Calcutta. Some dying under trees, others begging for water, and still others for food. The land rich in tradition leaves nothing for the people who are left with no choice but to sell their present for food. Annabhau’s call is to preserve the present and also help remember the past.

Maharashtracha Povada, written in 1947, is a povada in eight parts, encompassing 800 years of Maharashtra’s history. He begins with the geographical mapping of the state and by creating the physical setting of the history to come. In Mumbaicha Girni Kamgar (Mumbai’s factory workers) written in 1949, Annabhau traces the struggles and miseries of Bombay’s factory workers across the two regimes showing up the similarities of the apathy the workers faced.

<html5media>File:5AMajhiMaina_ShahirVitthalUmap_Lokgeet.mp3</html5media>

Mazi Maina Gavawar Rahili (Of my lover left behind) is a povada that speaks of such marginalisation and pain. The povada is about the lover that a migrant worker had to leave behind. The idiom of description reflects the desires that brought him to Bombay, of beauty and gold ornaments. But the lover knows of the poverty that keeps him estranged. He knows that he has added to his despondent story to the sad saga that is Bombay. The pain however is not new. He has carried it with him ever since he left for Bombay’s streets. But the poverty of Bombay is all that remains. Even the memory of the only beauty, he is able to remember. The poet relates the separation of the Marathi-speaking areas to a lover’s separation from his beloved who is in his village and he is burning here in Bombay far far away from her.

<html5media width="100%">File:MumbaichiLavani LokshahirAnnaBhauSathe PerformedByVihaan.webm</html5media>

Mumbaichi Lavani (Ode to Bombay) written in 1949, is the perfect example of how Annabhau deploys the aesthetic. Though called a lavani, this povada reflects the misery and destituteness that is Bombay. Metaphor after metaphor lays bare the truth of the lives of the 30 lakh people that make the city breathe. But despondence and ugliness is the bottom line. Nothing is beautiful in so much misery. This is the city where the red flag in the hand of the worker is taking the first step to make a free generation. In “Mum baichi Lavani” , as points of prosperity in Bombay, Anna Bhau mentions Malbar Hill, the abode of the rich, flying planes, vast roads etc. About the exposition of poverty in Bombay, he refers to manual labourers, dying horses of tongas, porters, unclaimed dead bodies, decayed human beings on the sea- coast, crowds of patients in W adia and K.E.M . hospitals, victim s of T.B. (Tuberculosis), V.D. (Veneral Disease), cholera, fever, cough and cannibals in a figurative sense.

LOKNATYA

Written largely between 1945 and 1952, Annabhau’s loknatyas were inevitably about exploitation and social relations that made up society. His audiences were an integral part of the idiom of his plays. His ten plays were performed hundreds of times to hundreds of thousands of viewers. Annabhau used the plays to address contemporary political issues. The plays were informative, critical, and analytical of the existing political situation and were in a sense, the locations for the creation of a responsive society. Annabhau used the plays to highlight injustice, ridicule oppressive exploitation, and social relations of the powerful castes. The plays also reflect Annabhau’s communist leanings. Worker capitalist interactions and the relations between the workers and the state were also popular themes.

SHORT STORIES

The short stories deal with particular human circumstances. These too are about modes of survival. The stories cover a wide range of characters, social conditions, and eras. Urban and rural, pre-independence and post independence. Workers, the poor, Dalits, and women make up the central characters. The tensions that wrought survival are strung tight through his stories. The alienation of the characters and the conditions of this alienation are dealt with in depth but with careful brevity. Till then, the Dalit has been portrayed as a gangster, a cheat, a thief, or an amoral sexual predator. Annabhau’s short stories try to remove the moral baggage that these categories carry and investigate and expose the manner in which Dalits are written into the public imagination.

NOVELS

Annabhau’s novels offer detailed descriptions of the natural surrounding of rural life in middle Maharashtra. His images of the geography and of rural scenery and life, of beauty and resilience, are used as part of the characters that inhabit his novels. The land as making the people. Tamasha, Waghya Murodia, barter system, the police station, jails, urban slums, form the locations and sometimes become the characters in his novels. The works are peopled with dacoits, rebels, and urban criminals. Never before have such protagonists found non-marginalised spaces in novels. His novels can be seen to be dealing with specific themes such as: Marxism, rural life, feminism, and revolution.

His work moved across village, town, city and nation and across feudal, colonial and the industrial land scape.

Further Reading:

- Anna Bhau Sathe by Bajrang Korde

- Anna Bhau Sathe by Baburav Gurav

- Dumdumli Lalkaar by Avinash Kadam

- The Life and Work of Anna Bhau Sathe by Milind Awad