Justice Lentin visits Kamraj Nagar, and What Happens Next

<gallery>

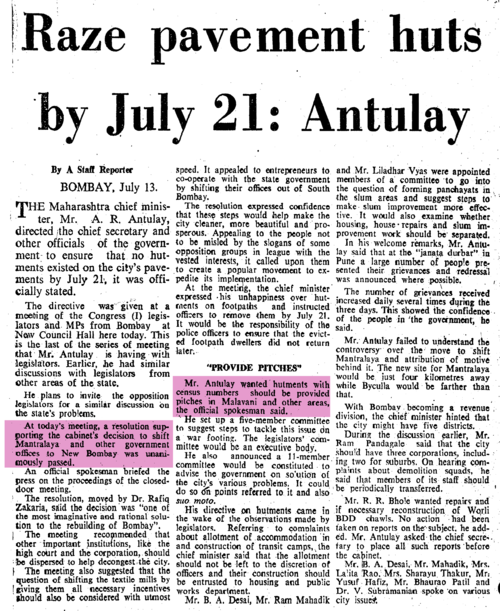

In mid-monsoon exactly thirty-six years ago, Chief Minister A.R. Antulay initiated Operation Demolition, whose objective was to bulldoze and evict pavement dwellers in a corridor "from the Airport to the Taj Hotel". On 14th July Antulay declared that these pavements will be cleared of its dwellers.

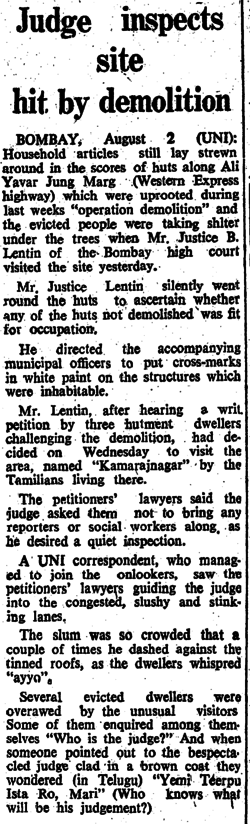

On the morning of July 23rd 1981, bulldozers ran over an estimated 1600 pavement homes, and the people in them were put in state transport buses and taken to locations outside the city limits, including to train stations such as Bhusawal and Solapur, where non-Maharashtrians were given tickets to "home" states. On July 23rd itself, the rights organisation PUCL obtained an interim stay on the demolitions and deportations, but they did not stop entirely. The stay was granted by Justice Lentin at the Bombay High Court.

On Saturday August 1st, amid news of continuing demolitions, Justice Lentin visited a basti in Vile Parle, on the now Western Express Highway, called Kamraj Nagar by its residents. Unannounced, and wearing a brown coat, he spent 90 minutes talking to people and instructing that unbroken shacks be marked with a white cross. Three days later, he passes an order instructing that people in Kamraj Nagar could return to marked huts, and that demolitions city-wide be put on hold till October 15, after the monsoons. Lentin would later write, "I resolved that if I could bend the law, even twist it, to ameliorate, be it in a little way, the lot of those who were helpless, for those who could not speak for themselves...”. Justice Lentin was at the Bombay High Court during the duration of 1975 till 1989.

The Centre for Education and Documentation (CED) on Battery Street was in those days a place where people doing archival research and journalists would gather practically every evening. Their discussions could end up at Gokul or in the papers the next morning. Among the participants was the young journalist Olga Tellis, writer of an anonymous column in the Blitz called "Garibi Hatao, My Foot!" that had been running through the Emergency years.

Meanwhile, PUCL has moved the pavement dwellers case to the Supreme Court, asking essentially for a more humane demolition procedure. In an unusual move that seems to stem from discussions at CED, Olga Tellis writes a letter to the Supreme Court in late August that makes a different, more radical claim than PUCL's, stating that the pavement dwellers issue was about a right to life and livelihood for all city dwellers. A PUCL report titled The Shunned and the Shunted lays before the readers the arguments it was making in the court as well the difference of approach between their's and Olga's on the issue of pavement dwellers.

<pdf width="250" height="250">File:1983_Shunned_and_Shunted_PUCL_Report.pdf</pdf>

Thus a range of strong positions are taken up by people in city institutions in these few weeks, addressing the perennial Bombay question of housing or lack of it. Some months later, Antulay has to resign as CM because of a high court judgement on the cement scam, also by Justice Lentin. This milieu forms the backdrop for two extraordinary Bombay films released in the following years: Kundan Shah's black comedy Jaano Bhi do Yaaro, and Saeed Mirza's housing-courtroom tragedy Mohan Joshi Hazir Ho! Olga Tellis' letter to the court is accepted as a public interest litigation, and transforms into the landmark "Olga Tellis case", which has effects on legal debates and the teaching of law, to this day.